A few weeks ago I took a break from Constant Companion, Daughter, and the three kitties and the mundane, whatever I do with my life everyday and left town. Like many others, after the pandemic I made a mental list of places I’d like to visit again or for the first time. New Orleans is one of those places. I mentioned this desire to a grad school friend who was mired in tons of student papers in one of our infrequent phone calls; she jumped on it. Over her spring break we met in the Crescent City for a few days of exploring. What a great get-away. You know when you were friends long ago, went to aerobics class after work, laughed over bum dates, and stayed up nights copy-editing dissertations! After all those years, I think we caught up where we’d left off.

When I travel, I usually like seeing the usual places and sites. I also thoroughly enjoy the unexpected. Looking around I see details on and around buildings and more like murals. My visit to New Orleans was no different.

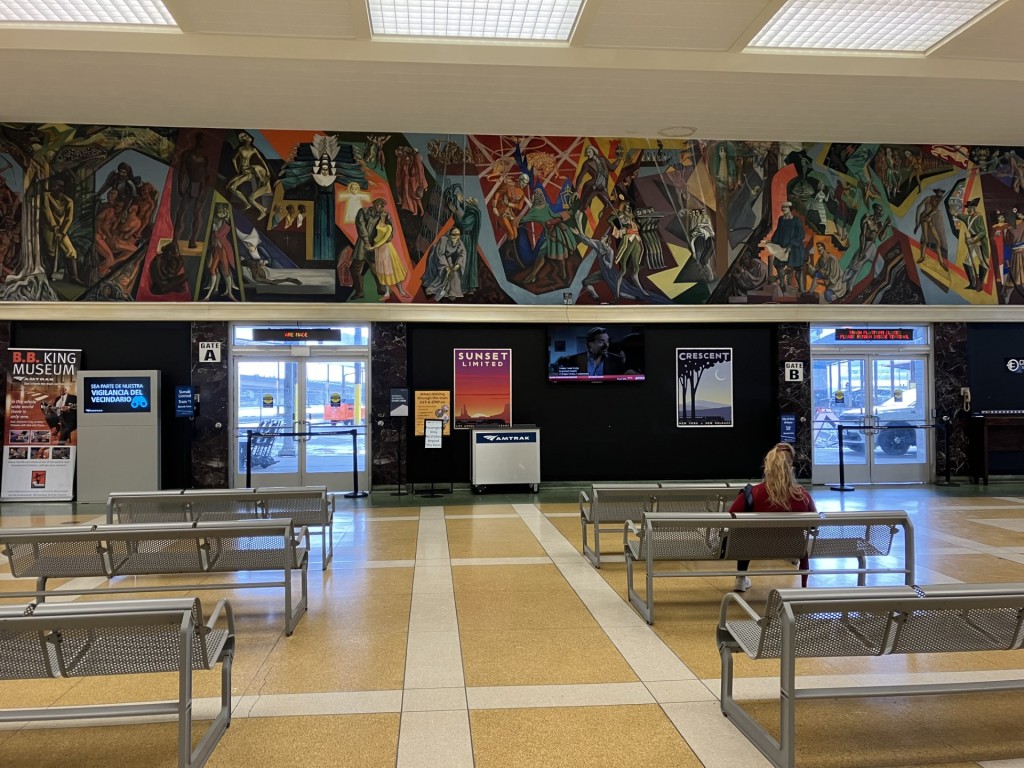

I flew in; my friend took the train from Mississippi. Almost the first thing I noticed when I entered the shared Greyhound/Train Station to meet her were the immense murals overshadowing the expansive and very empty lobby. The brightly colored images progressing around the four walls included settlers, soldiers, Klansmen, scientists, sharecroppers, and more telling the story of the city.

Each panel is over sixty feet long conveying different themes including “Exploration,” “Colonization,” “Conflict” (or “Struggle”), and “The Modern Age.”

Artist Conrad Albrizio visually captured the four hundred years of Louisiana history in 1954. Albrizio, known for his Works Progress Administration (WPA)-funded murals in locations throughout the South, was Louisiana State University’s first professor of painting. This mural, one of the largest in the United States when it was completed, was Albrizio’s last and is considered to be his best-known work. Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, it was restored by the New Orleans Building Corporation. The murals in the Union Passenger Terminal have been called some of the city’s most important treasures of public art.

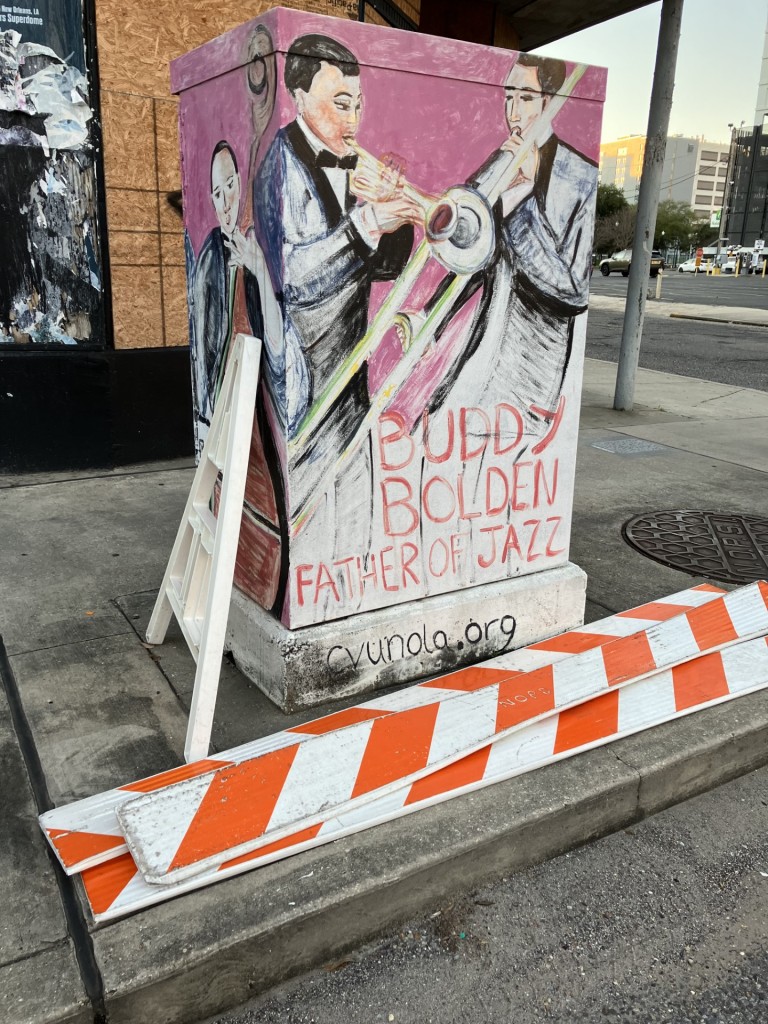

Walking to and from the train station, I noted several murals. Standing out was Brandan Odums’ massive mural of jazz pioneer Buddy “King” Bolden on the façade of the former Little Gem Saloon (445 S. Rampart St). Bolden’s use of syncopation, his ability to improvise, and his use of blues structures led him to be accepted as the first legend of jazz.

By the late 1890s, he led the most successful band in New Orleans. Buddy Bolden’s career in the first decade of the 20th century was short. Health issues robbed the city of this talented musician whose image is captured in several nearby locations.

The striking, brightly colored mural of Louis Armstrong by internationally known Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra near our hotel called out to me. The three-story image is painted on the back wall of a century-old building near the corner of Gravier and O’Keefe streets. This area of the city was known for jazz-era nightclubs and also the tailor shop owned by the Karnofsky family, the young Armstrong’s employers. The building is being converted into a boutique hotel. Kobra’s uses repeating squares and triangles to bring to life the famous people he depicts in his images.

On the following days, we just happened upon lots of buildings, along with generous residents who kindly provided private tours along with history lessons. Day One was Museum Day. After our lengthy visit to the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (a must-see in New Orleans), we were admiring a neighboring building near Lee Circle (note the empty column from which a statue of Robert E. Lee towered for many years). The outstanding structure, the the Howard Memorial Library, now the Patrick F. Taylor Library, with thick walls, a semi-circular arched entrance, and rounded towers was designed by esteemed American architect Henry Hobson Richardson, a New Orleans native, and built after his death. Architects and critics have come to describe his unique and revival style as “Richardsonian Romanesque.”

The Howard Memorial Library opened to the public on Mardi Gras Day, 1889. When it was dedicated, the Louisiana Historical Association (LHA), a historical society of confederate veterans, was created in the adjacent Howard Memorial Hall (1890), now known as the Confederate Memorial Hall Museum. After several transformations (radio station, office spaces and a law firm), restorations, and a name change in 1989 that marked its centennial, the Patrick F. Taylor Library was acquired by the University of New Orleans Foundation to become part of the Ogden Museum.

We were amazed by the sweeping staircase that led upstairs to the former library and its dome-vaulted, wooden ceiling with 16 dragon heads jutting out toward the center of the room from the rounded walls.

Our post-lunch rambling took us through lovely Lafayette Square, the second-oldest public park in the city. The square was laid out in 1788 as Place Gravier. After 1803, it became the central square of the English-speaking part of the city and was long the center of political life in New Orleans. The focal point of Lafayette Square is the bronze statue of Henry Clay, created in 1863 by the American sculptor Joel T. Hart. The statue honors Clay, a prominent statesman who narrowly lost the presidential elections of 1845 was moved to its current location in 1900.

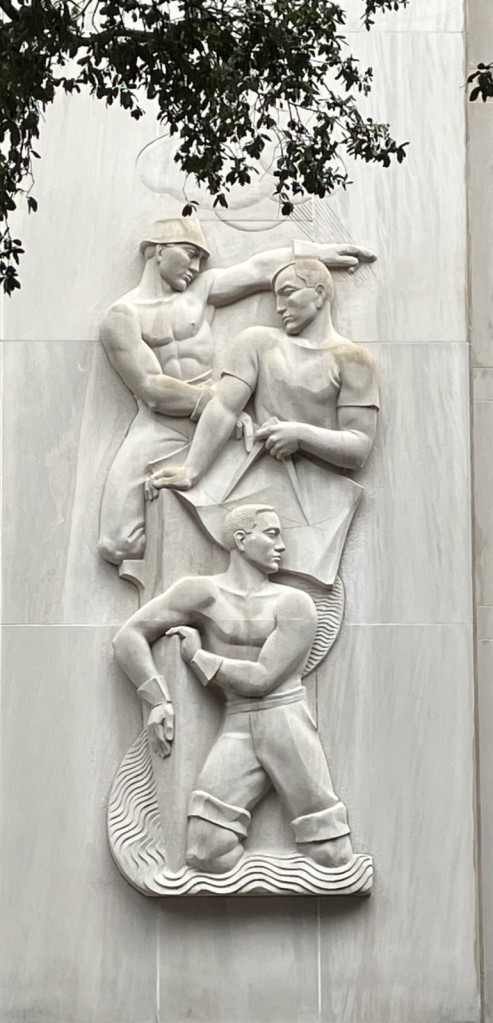

Two federal buildings fill two sides of the square. One of four monumental marble eagle statues first caught my eye and drew me to the F. Edward Hebert Federal Building (built from 1935 to 1939). As I walked around, I was drawn to the two outstanding WPA period limestone sculptures decorating the building’s façade. “Flood Control” (right) was created by Karl Lang. “Harvesting Sugar Cane” (left) was created by Armin Scheler.

Then I looked up at the John Minor Wisdom U.S. Court of Appeals Building (1915), originally the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse. Four colossal copper and bronze sculptures, created by the renowned Piccirilli Brothers, rise high above each of the building’s corners. Called “History,” “Agriculture,” “Industry,” and “Arts,” they are popularly known as “The Ladies;” each figure holds an item associated with the concept it represents. “History” wears a bonnet; “Agriculture” holds a cornucopia; “Industry” holds a tool; and “Arts” holds a flower.

Day Two was the French Quarter. We were compelled to start the day with coffee and beignets at Café du Monde followed by a stroll through the French Market.

There we met Charles E. Garrison, the POET of New Orleans (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kwnv-1gC1GY), just setting up his table in the Market. He started our day with a special inspirational poem.

Along the way, another mural that caught my eye. “Connections,” located at the French Market flood wall, speaks to the connection between Canada and New Orleans. This mural was a cross-border collaboration between the City of New Orleans and the Consulate General of Canada in homage to the shared history, people-to-people linkages, and Cajun-Acadian connections. Designed by Canadian artist Chantelle Trainor Matties and painted by New Orleans artist JoLean Barkley, it depicts wildlife in both regions and uses abstract blue and green tones to depict the reliance of both Canadians and New Orleanians on water. Ironically, the imagery is drawn from the First Nations of the Northwest Coast, not the Laurentian French communities who resettled in Louisiana.

I was drawn to many other buildings and features on our brief visit to New Orleans.

Around the corner from our hotel was the Immaculate Conception Jesuit Church (130 Baronne Street). As I admired the façade (in Venetian Gothic Revival and Moorish Revival styles), a passing resident urged my friend to take a look inside; we did and we were awed. The present church, completed in 1930, is a near duplicate of an earlier 1850s church on the same site.

At the entrance I was struck by several figures, St. Francis, St. Patrick, and a mosaic shrine to the Virgin. I do not know if it was Our Lady of Perpetual Help or Our Lady of Prompt Succor who is credited with two miraculous interventions in the city of New Orleans (1788 and 1815).

The altar is a work of art. Made of gilded bronze and designed by James Freret of New Orleans, it won first prize in the Paris Exposition of 1867. High above the altar is “Mary’s Niche,” a solid-marble statue of the Blessed Virgin standing in front of a gilded, lit background, flanked by statues of four other saints.

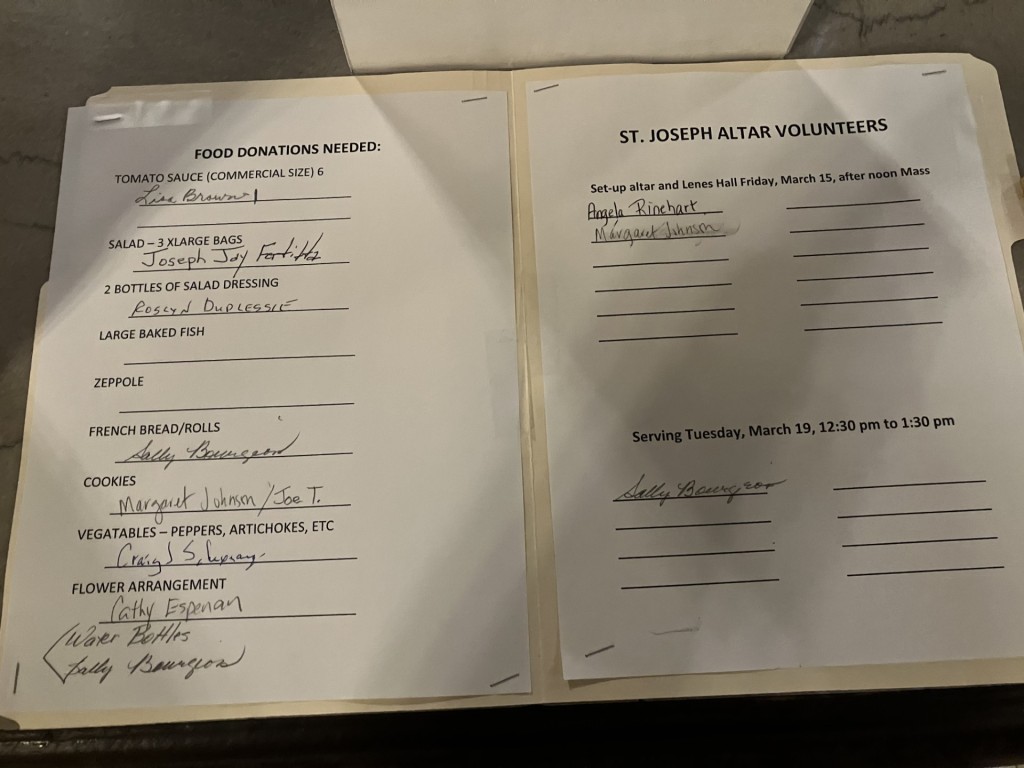

As we perused the usual paperwork near the church entrance, I was struck by the loose leaf binder with lists of what parishioners would be contributing to the annual St. Joseph altar. I was introduced to Italian-American traditions associated with St. Joseph Day celebrations when I worked in Cleveland, Ohio, and wished we could stay longer New Orleans for the feast day. I guess that’s the reason to return another year!

As we trekked the streets, my eyes were frequently drawn upward by a small, circular structure reminiscent of a white Greek temple. On our last morning we learned it was the Hibernia National Bank (812 Gravier Street). When we reached the building before opening time, a gentleman let us in to one of the lobbies, gave some history, and recommended we return after 9 a.m. when the bank would be open. I did that and was transported back in time by the large, gracious lobby.

Hibernia National Bank was founded by Irish immigrants in 1870 and took its name from “Hibernia,” Latin for the island of Ireland. The 23-story Renaissance-style building, completed in 1921, was New Orleans’ first modern skyscraper. It was the tallest in Louisiana until the State Capitol building in Baton Rouge surpassed it in 1932. The white Greek Revival cupola, 355 feet in the air, once served as a navigational beacon for ships along the Mississippi River.

Hibernia National Bank was Louisiana’s largest bank until it was bought by Capital One in 2005. Following the purchase, the building’s first floor bank lobby remained in use while the upper floors became vacant. Since 2011, the upper floors have been converted into luxury apartments. The cupola was restored, and LED lights were added.

I feel fortunate to visit this historic bank building’s lobby. The bank branch will be closed soon, if it has not done so already.

In three days, we walked many miles, enjoyed some quintessential New Orleans meals and saw some interesting sites. Here are a few more:

This bronze statue by local sculptor Bill Ludwig of “Ignatius J. Reilly,” the protagonist in John Kennedy Toole’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, A Confederacy of Dunces, waits under the clock in front of the former site of the D. H. Holmes Department Store (1849-1989) on Canal Street.

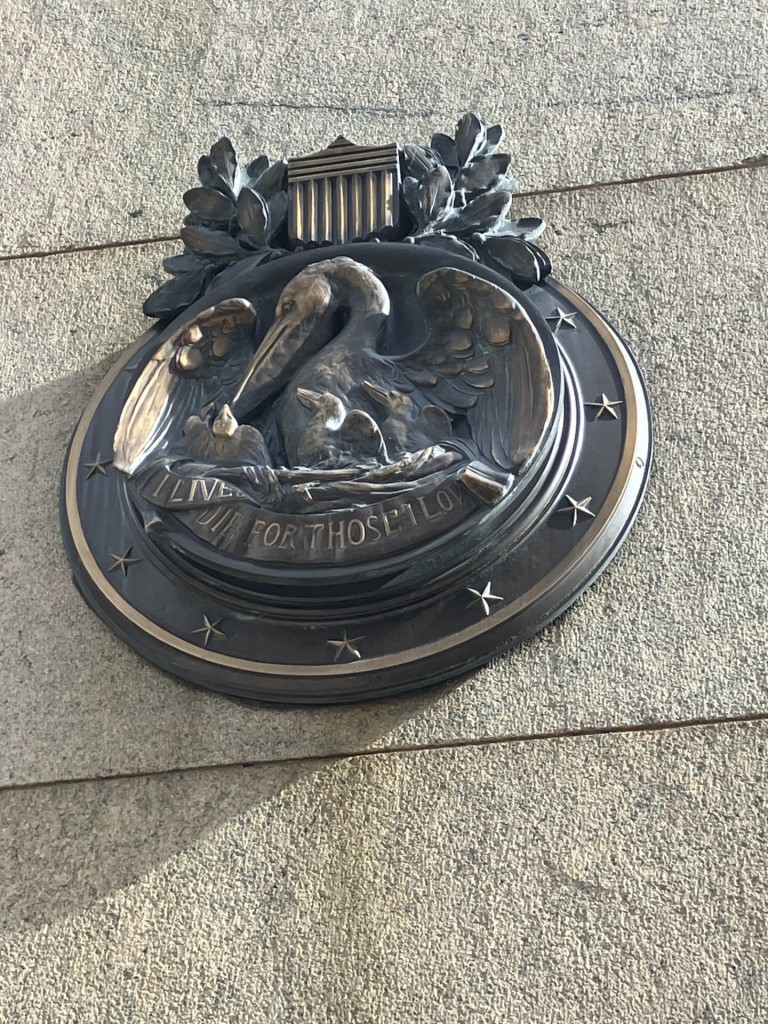

Another sculptural feature was this rondel showing a mother pelican feeding her chicks (see 5-11-23 post for this story) at Whitney Banks.

The cherubs dancing along the entry to the still-operating Orpheum are a sight to be seen.

We did all the usual stuff, too:

Walking tour with quintessential buildings with wrought iron balconies

The talking mime at Jackson Square.

Opposite our hotel was an empty building. This was the view from our window. New Orleans is not a city where you can be lonely!

And whatever city had a humidor next to the ATM and waters in the convenience store?

Many New Orleans residents kindly opened their city to us – Terence at the Taylor Library, the lady on the street outside the Immaculate Conception Jesuit Church, Charles E. Garrison in the French Market, and the preservationist at the Hibernian bank.