It’s nice to plan a visit to reconnect with friends you’ve not seen for a while. Constant Companion and I did that recently, though we did not know “who” we would actually be crossing paths with.

We continue to check art exhibits off our list of post Art Week excursions, and isn’t it funny, new destinations keep getting added to the list. Thanks to the local NPR station and a random full-page advertisement in the New Yorker, we took a drive north to Palm Beach to the Society of the Four Arts to see “Past Forward: Native American Art from the Gilcrease Museum” in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The Society of the Four Arts is a delightful campus with numerous buildings with a 1936 exhibition building housing exhibits, as well as a library, education building, and sculpture garden. We moved to South Florida twenty-six years ago, the longest residence in any location for the three of us. This exhibit spoke to us loudly because we both had connections to the wonderful Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma as well as connections to a number of the artists whose work we expected to meet at the exhibition.

Constant Companion and I met and married in Tulsa. One of our early dates took us to the Gilcrease where we wandered its spacious green grounds and visited the museum. Of course, we returned many times. The museum holds one of the largest collections of art of North America.

In this exhibit, Charles Banks Wilson’s portrait of Thomas Gilcrease overlooking the Osage hills on the Tulsa’s north side, the location of his namesake museum, greeted visitors as they entered. I felt as if Mr. Gilcrease was greeting me with a warm Oklahoma “Hello.” Note the piece of pottery in the forefront.

My Gilcrease was part Muscogee Creek. His land included “The Glenn Pool,” one of the richest oil deposits in the US. He used much of his wealth to amass a priceless collection of arts and documents representing American, especially pre and post-contact Native American, culture.

Seeing a collection of artworks from the museum’s vast collection reminded me of the distinct privilege I enjoyed, working with Native American artists and cultural specialists in several museum projects in Oklahoma and again, here in South Florida. One’s points of view and perspectives are expanded through exposure to approaches taken by different cultures. This aspect of my work has certainly shaped my practice as a museum professional, and I think a human being.

Slowly walking through the galleries, I remembered a meeting of some arts organization early in my stay in Tulsa. Ruthe Blalock Jones, at that time a professor of art at Bacone College, warmly greeted me, a long-time friendship followed. I finally bought one of her prints at the famous annual Indian Art Market in Santa Fe many years later. Ribbon Dance, her diptych in this exhibition, took me back to our many conversations as well as my work helping restore and revitalize the Creek Council House in Okmulgee, Oklahoma. Stomp dance and shell-shaking (see turtle shells around the girls’ ankles) is a tradition. Two sashes like the ones worn by the dancers are at my side on a file cabinet.

In Okmulgee, I was introduced to the work of Acee Blue Eagle, thought he had passed long before I could have met. He also studied and taught at Bacone. I learned of his work and his standing as an artist and representative of Native Americans who spoke extensively about their life and cultures across Europe while working in Okmulgee.

One of our prized possessions is this drink set that he made for Knox Industries. Before my time, certain manufacturers gave promotional items to entice customers to purchase their products, such as serving bowls in boxes of laundry detergent. Acee Blue Eagle’s paintings were used on this set of pitcher, glasses, and tray were gifts with a 10-gallon purchase of gasoline. Somewhere out there are matching dinner dishes.

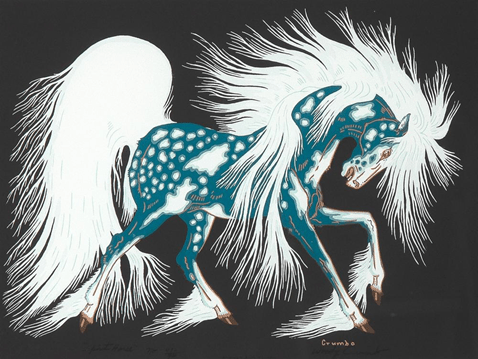

When I saw this Peyote Messenger Bird #1 by Woody Crumbo, a vague memory of an afternoon visit with Mrs. Crumbo. It was a delightful visit during which I learned about the work and life of Mr. Crumbo. I left with two prints that for many years hung in my museum office. This image relates to the sacraments of the Native American Church.

Somewhere along the way, I picked up postcards with Crumbo’s “Spirit Horse.” Both Constant Companion and I gave it as small gifts when we traveled overseas.

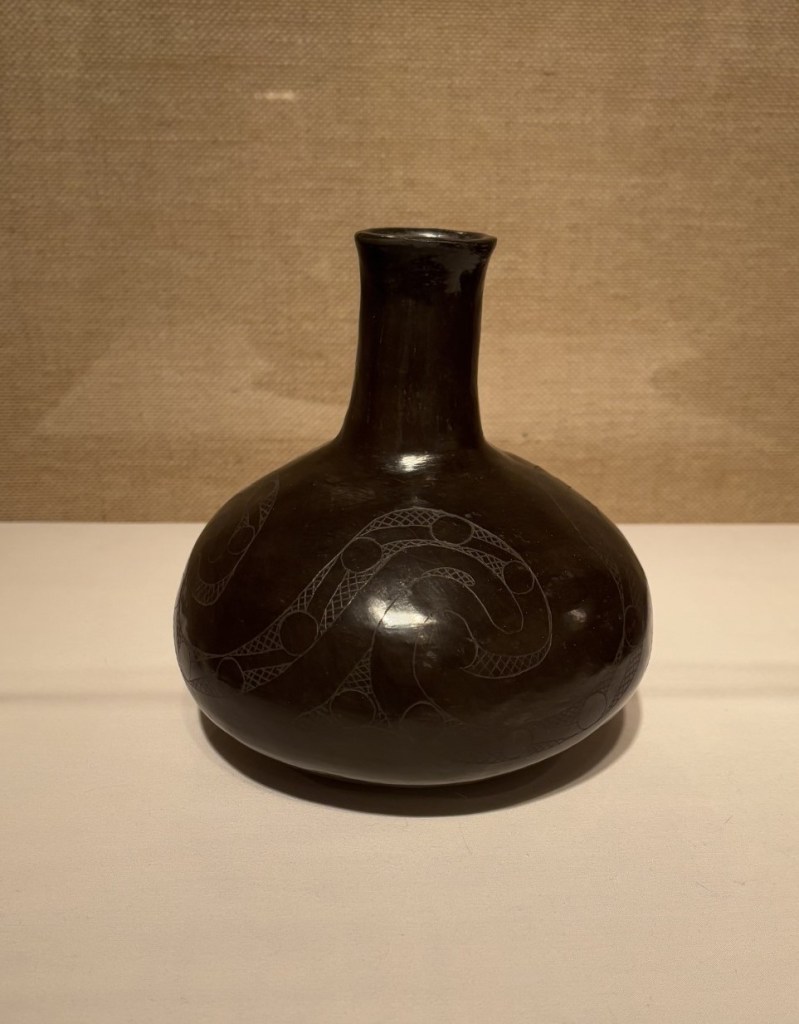

Jeri Redcorn is an amazing potter, responsible for reviving pre-contact Caddo pottery techniques perfected in North American long before the Europeans arrived. Her work takes patterns from excavations found west of the Mississippi River. We met Jeri and her husband when I was at the University of Oklahoma and enjoyed crossing paths with them in town and at numerous events. Look back at the portrait of Mr. Gilcrease.

Two non-Native artists whose work was included in this extensive exhibit were George Catlin and Alexandre Hogue. I did a deep dive into Catlin’s work when I curated the exhibit, Seminole Portraits, Reflections Across Time at the Frost Art Museum, FIU. The focus of the exhibition was on portrayals of the Florida Seminole with 19th century works by Catlin and other non-Native artists and, perhaps, more importantly, the works of present day Florida Seminole artists.

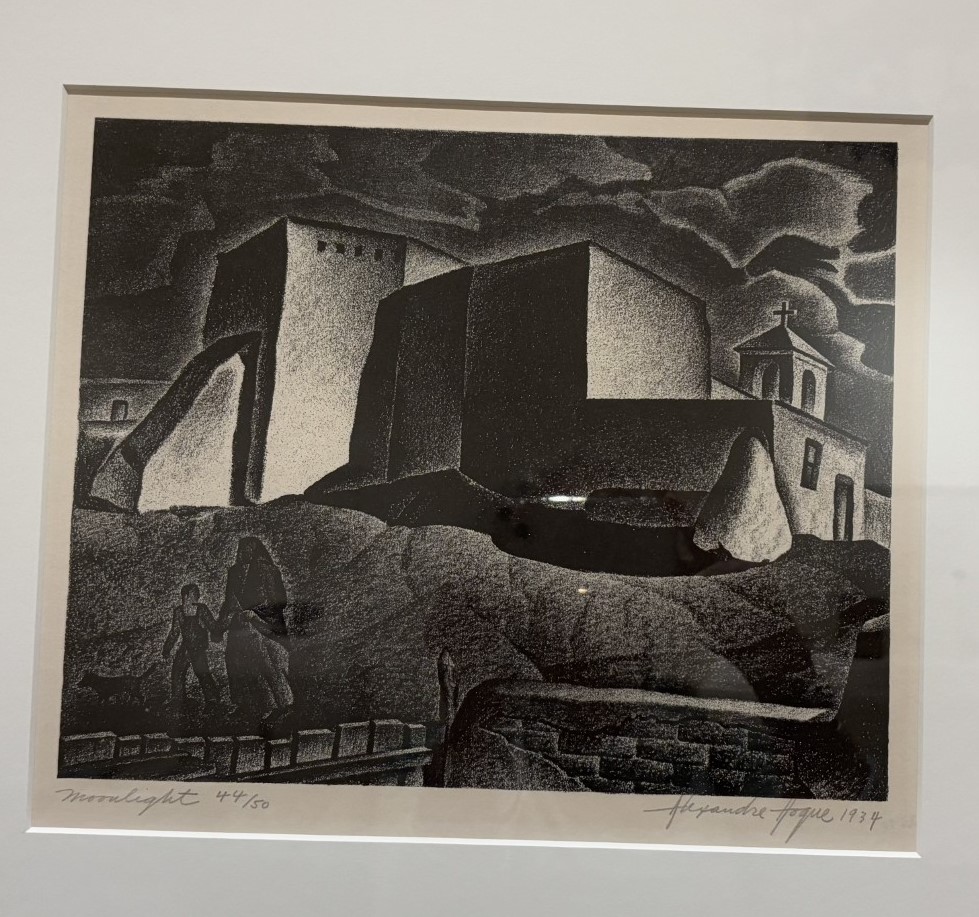

Constant Companion and I “met” the work of Alexandre Hogue when we were both at the University of Tulsa. Hogue was a realist painter whose landscapes focus on the American Southwest and south central United States.

A reflection … It’s funny. One does not often appreciate or acnknowledge the extent of their accomplishments and those who contributed to them. We do not take the time to reflect on the many people who have crossed our paths through life. Taking this nostalgic visual journey a few weeks ago is perhaps one step on the road of realizing who I am and what I have done. It certainly reminded me of what I consider a privilege to have known the Native American artists and others in Oklahoma and Florida.

Thanks, Annette, for this inspiring reflection on the people and experiences that have made us who and what and where we are today!

LikeLike